Paper review: Shadow Kernels

Shadow Kernels: A General Mechanism For Kernel Specialization in Existing Operating Systems

Application selectable kernel specializations by Chick et al.

Abstract

Chick et al start their paper by noting that existing operating system share

one single kernel .text section between all running tasks, and that this fact

contradicts recent research which has proved from time to time that profile

guided optimizations are beneficial. Their solution involves remapping the

running kernel’s page-tables on context switches and expose to user-space the

ability to choose which “shadow kernel” to bind its process to. The authors

have implemented their prototype using the Xen hypervisor and argue that, thus,

it can be extended to any operating system that runs on Xen.

Introduction

The authors argue that in a traditionally monolithic operating systems, system

calls are fast because they don’t require swapping page tables and flushing the

TLB’s caches. However, the disadvantage of such system is the fact that

per-process optimization of the kernel is now impossible. To fix the

discrepancy between relevant research on profile guided optimizations and the

apparent lack of embracing it, they introduce “shadow kernels”, a per-process

optimization mechanism of the kernel’s .text section.

Motivation

The authors of this paper highlight three benefits of “shadow kernels” that have motivated them.

Firstly, the already mentioned recent research into profile-guided

optimization. One of the unsolved issues of such optimization is that it must

be based on a representative workload. They argue that, Shadow kernels allow

applications executing on the same machine to each execute with their own

kernel that is optimized with profile-guided optimization specific to that

program. And thus, the problem about representative workload is solved,

because you presumably know the profile of your own program and you no longer

need to care about other processes running on the same machine.

Secondly, scoping probes. It is well known that Linux has multiple

instrumentation primitives, for instance Kprobes and DTrace. The authors argue

that when one process may want to be instrumented, every other process in the

system is also impacted by the overhead of installing the primitive. In

contemporary operating systems it is simply impossible to restrict the scope of

a probe to a single, or a group of, process(es). Shadow kernels again present a

solution here by replacing the pages of the affected process’ kernel .text

region.

Finally, the third factor that has motivated the authors is about overall optimization of the kernel and its fast paths. They argue that while security checks are in the kernel there is a strong case for trusted processes, which do not necessarily need the protections that are in place and in those cases the additional checks are a bottleneck` to their performance. With shadow kernels, it is possible to remove security checks from the address space of one process while leaving them intact in all other processes.

Design

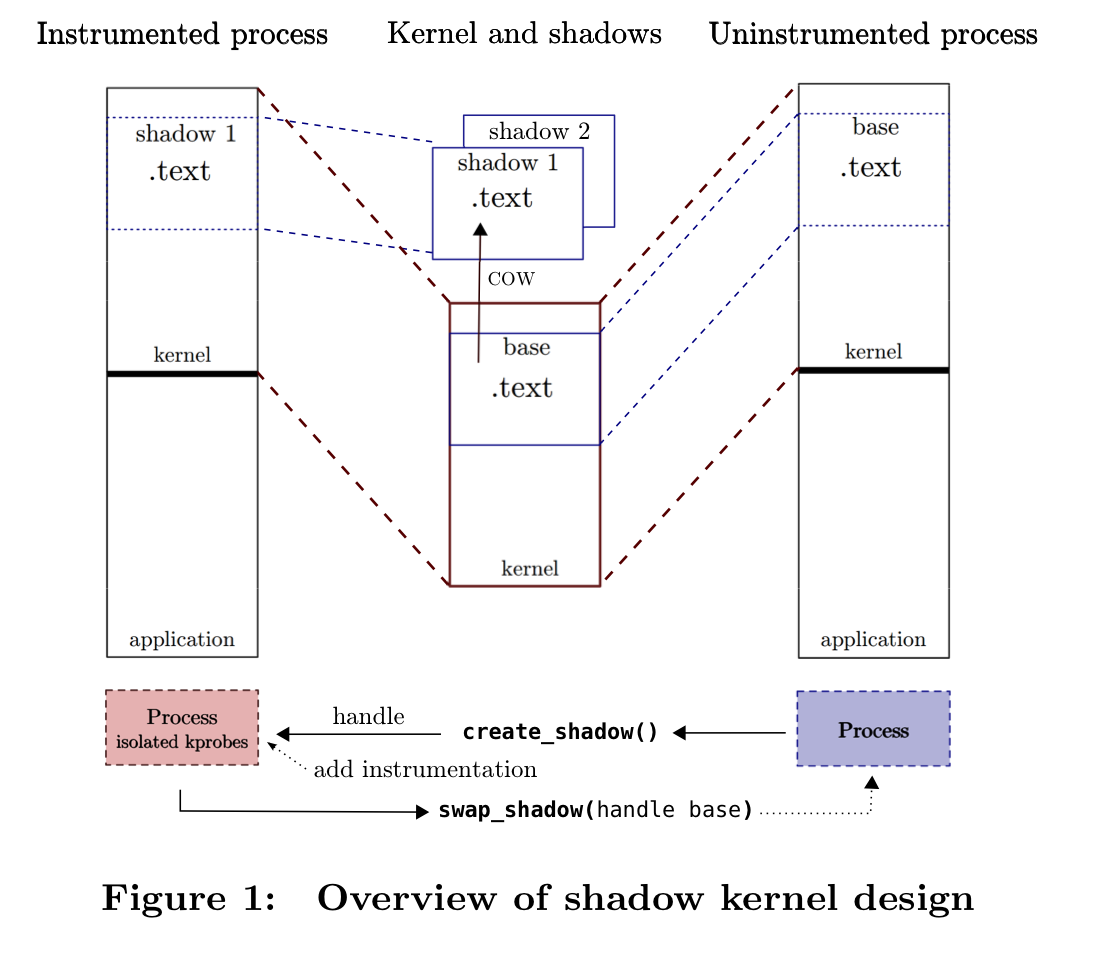

The most important parts about the shadow kernel design can be nicely summed in

the authors’ own words: An application can spawn a new shadow kernel through

a call to a kernel module. This creates a copy-on-write version of the

currently running kernel, which is mapped into the memory of the process that

created it. As a process registers probes, the specialization mechanism makes

modifications to the kernel’s instruction stream. Due to the use of

copy-on-write, every page that is modified is then physically copied, leaving

the original kernel text un-touched. Modified functions are replaced using

standard mechanisms of either rewriting the entire block if the “replacee” is

shorter or the same length or using an unconditional jump that is easy to

branch predict.

The above figure gives us a little overview on the actual architectural details of this novel technique.

One of the more interesting problems with this approach is dealing with kernel code that is not bound to a single process (think, kworkers, interrupts and schedulers). The authors mention that is difficult to just go ahead and remap the pages because other processes may want to augment the same page in a different way. The solution they propose is giving up isolation and using the code of a “union” shadow kernel that contains all of the probes.

Implementation

Probably one of the most fascinating I’ve read in this paper is the fact their entire implementation is 250 lines of code entirely implemented as a Linux kernel module. Pretty much of the implementation is specific to the Linux kernel thus, and I don’t think describing it here would be of much value, rather anyone interested can read the paper and find more detail about how the implementation adheres to the Design outlined above.

Evaluation

Furthering motivation, the authors show that probing the most popular kernel function called across all CPUs reduces single thread performance by 30%, and it keeps worsening if you probe the top three functions to 50%. They tested their setup monitoring the performance of memcached and installing probes in an unrelated process. From this result, it is clear that some technique to solve this, is worthwhile.